Who's Lighthouse Bureau? Could these be the Confederates who smashed the lenses? The same fine folks who blew up towers? The Southern gentlemen who systematically destroyed what the Good Guys in the federal government had built?

If you limit your reading to official Union records of the Civil War, it would certainly seem so. But the Confederacy also left records, which, until 1990, were apparently untouched by researchers. These records show that the Confederate States government aggressively preserved its vital lighthouses, and maritime legacy left by the Union. Unfortunately, the period of unpleasantries, which gave birth to the Confederacy, also brought on wholesale devastation to the South’s aids to navigation.

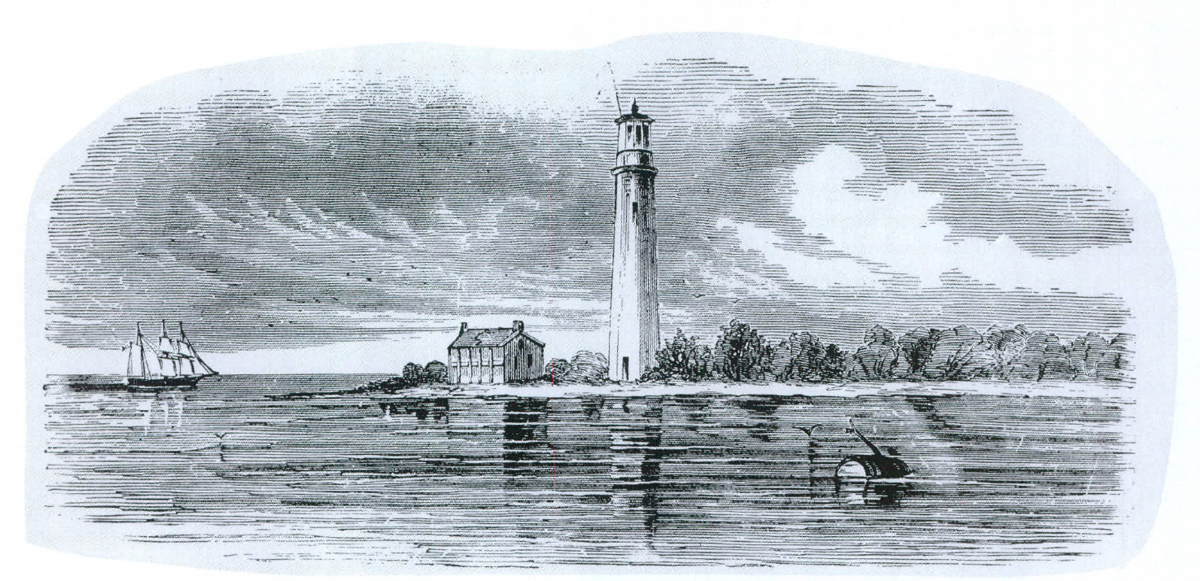

The South, perhaps more than the North, was dependent on successful and safe ports, which lighthouses helped provide. The Northern economy, nearly self-sufficient, provided its population with both food and fine manufactured products from within its borders. The South, on the other hand, was almost entirely agricultural, exporting cotton and tobacco and importing European and Northern consumer goods. Cotton was the singular American commodity, accounting for far greater than half the value of all U.S. exports in 1860. The leading cotton states, bordering the Gulf of Mexico, annually sent almost a million tons of cotton to sea just before the war. While the South lacked a comparable railroad network, it enjoyed a vast navigable river system unparalleled in the North. Reaching hundreds of miles inland, rivers from the richest land in America connected two-thirds of the United States to ports of the Gulf. An efficient system of lighting the Southern coast was critical to this commerce. Congressman Jefferson Davis had worked diligently in the 1840’s to insure that Southern coasts were well marked by a system of efficient lighthouses. As President of the Confederate States, he acted quickly to establish a Lighthouse Bureau with one of his top naval officers as chief.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis

The U.S. Treasury Secretary knew who was paying the federal bills. The South’s foreign trade by the 1860’s had become the foundation of America’s economy, supplying the government with three-fourths of the federal budget. The U.S. Lighthouse Board had nearly completed its modernization of the lighthouse system when political hostility came to a head. By 1859 every chandelier of ancient reflectors had been replaced by modern Fresnel lenses (a few reflector lights remained in minor range lights). The inefficient lightships had been replaced where possible by screw-pile lighthouses or by more powerful lights ashore. Tall first-order lighthouses such as the 200-foot tower at Mobile’s Sand Island had just started to settle into the tidewater muck. Only a half dozen or so southern lighthouses approved by Congress remained to be erected, with most delayed by ancient colonial land grants and other title disputes. The American lighthouse system was approaching its zenith when a more widespread land dispute interceded.

State Lighthouse Establishments During Secession

A principle issue for secession from the Union was sovereignty over former federal facilities, which the states felt had been more than paid in full by local tax revenues. The newly independent states moved quickly to seize forts, arsenals, customhouses and lighthouses. It was important to continue “business as usual” at the lighthouses in order to keep vital trade following without interruption. In Alabama, one of the first states to follow South Carolina to independence, the governor issued immediate orders inviting former U.S. government employees to continue their duties under state control. U.S. Navy Lieutenant E. L. Hardy, lighthouse inspector at Mobile, declined the offer when the state collector delivered a polite ultimatum on January 21, 1861: “To obviate difficulties and to prevent embarrassments that may arise from conflicting authorities in the Lighthouse Establishment with the limits of the State of Alabama, I do hereby notify you that in the name of the Sovereign State of Alabama, I take possession of the several Lighthouses within the State….” Alabama appointed its own inspector, R.T. Chapman and, lacking local directives, instructed state keepers, “In the discharge of your duties, you will be governed by the [c. 1857] laws, rules, and regulations of the United States…so far as they are applicable.

State by state, lighthouses migrated peacefully from federal to local control, with the exception of three towers at the Dry Tortugas and Key West, which were held by Union forces throughout the war. Neither keepers nor mariners saw any difference in operations. Inspectors inspected, engineers repaired and keepers were paid-in state funds.

By February 1861, the movement was well underway to tie seceding states together into a loose organization similar to the “firm league of friendship” created by the 1777 U.S. Articles of Confederation. On February 8, delegates adopted (essentially) the U.S. Constitution, appropriately edited to preserve the values of the South, and all U.S. laws, which did not contradict the new law of the land. One of these laws was, of course, the 1789 act authorizing national support of lighthouses to encourage prosperity and maritime commerce. However central control was not immediately established. Local customs collectors continued to manage lighthouses under their jurisdiction, often remaining under state control until the C.S. Treasury Department was able to take over.

Word of these occurrences filtered slowly down to keepers. On March 31, keeper Manuel Moreno at the isolated Southwest Pass of the Mississippi River knew very well that something was going on 120 miles upriver at New Orleans. Hearing rumors from pilots on stem tugs, he complained to New Orleans collector Frank Hatch, ”I am in this deserted place, ignorant of what is transpiring out of it.” The entire South was arming and he could not possibly be left out of the coming fray. “We ought to have about six muskets and a few pistols, and Powder and Balls, so as to be ready, at all times to resist any attack.”

The U.S. government tended to disagree with the Southern activities and, at least on paper, administered a parallel lighthouse establishment in the South throughout the war. At the Egmont Key Lighthouse, guarding Tampa Bay, keeper George Rickard was instructed by the Confederate collector to deceive the Union Navy and “keep up such relations with the fleet as would induce them to allow him to remain in charge until such time as the property could be safely removed.” When Union Blockaders went off in chase of sails, Rickard stripped the lighthouse station and buried the lighthouse lens “in the vicinity of Tampa.” When U.S. Navy Lieutenant Joseph E. Fry, inspector at New Orleans, resigned his commission on January 26 (the date of Louisiana’s secession) the Secretary of the U.S. Lighthouse Board asked the Treasury Department if a replacement would be requested from the Navy Department. The question was almost rhetorical and may have indeed been intended to test the federal Navy’s attitudes toward officers who resigned their commissions.

Egmont Key Lighthouse at Tampa was placed out of commission by the keeper.

That Secretary was Commander Raphael Semmes, U.S.N., an Alabamian and sailor of reputation who had felt for years that he was detailed to a dismal job of navigating a desk. A Confederate Congressional committee invited Semmes to resign his federal commission in favor of allegiance to the South. On February 15 he reported for duty at Montgomery, two days after the Electoral College affirmed Abraham Lincoln’s election to the Presidency. Semmes recommended a Southern organization similar in makeup to the U.S. Lighthouse Board but, for the sake of efficiency, more compact and under complete control of the Navy. While he was detailed to the North to buy gunboats, the Confederate Congress passed an act on March 6 establishing his Confederate States Lighthouse Bureau, its chief officer to be a captain or commander of the C.S. Navy.

Raphael Semmes

The new agency stumbled into action. C.S. Treasury Secretary C.G. Memminger recommended Semmes to President Jefferson Davis on April 10, 1861, although it appears that Semmes had already reported for duty as early as April 4. For Semmes, being a bureau chief meant a new desk but the same old sedentary job, and at a time when his new nation needed men of ‘salt’ and action. He had hardly rigged his office and shipped a clerk before shouts of “Sumter! Sumter!” rose over Montgomery on April 12. War had the audacity to start without him!

His only action of even minor significance (besides ordering some rather smart-looking stationery) as Father of the C.S. Lighthouse Bureau was to recommend division of the Confederacy into four lighthouse districts. District boundaries and headquarters are unclear in surviving documents, since the districts endured only a few months. The First (New Orleans) and Third (Mobile) Districts were in the Gulf of Mexico, constituting about half of the new nation and all the largest, most strategic cotton ports. The Second and Fourth Districts were apparently on the Atlantic Coast. Since his plan was presented and accepted by April 15, these districts may not have included the “border states” of Virginia (seceded April 17) and North Carolina (May 20).

Had the Lighthouse Bureau not begun dissolving almost immediately it might have later incorporated scientist and Army specialists, as did the U.S. Lighthouse Board. Semmes had no immediate use for engineers (perhaps he never liked the landlubbers) and quickly submitted the names of four top Navy lieutenants to fill the posts of district inspector. None of these ever reported for duty. Semmes did hire a civilian chief clerk, Edward F. Pedgard, who came aboard just in time to see the boss depart for war. Semmes left Montgomery on April 18 to outfit and command the commerce raider CSS Sumter at New Orleans. But this was not the last of Semmes’ involvement with lighthouses.

Secretary Memminger reported to President Davis that Semmes was “withdrawn from the Lighthouse Bureau for active service” and that several of the lieutenants he recommended were also desired by the Navy Secretary. He recommended Commander Ebenezer Farrand of Perdido, Florida, as the new bureau chief and Lieutenants W.G. Dozier for the First District inspector, J.D. Johnson for the Third District and J.R. Eggleston for the Fourth District. The Second District inspector job remained vacant for the remainder of the war. The inspectors were returned to the C.S. Navy on July 11, 1861, with the caveat, “Whenever the lights are restored, their services will gain become necessary.”

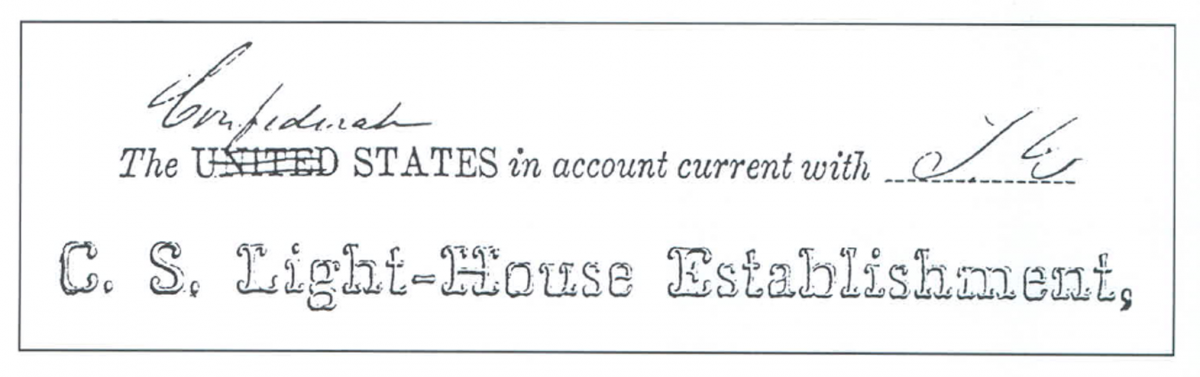

Early Confederate Paperwork

National events occurred at a rapid-fire pace and change continued to disrupt the Lighthouse Bureau. The Treasury Secretary appointed Thomas E. Martin as Chief Clerk, replacing Pedgard, on May 1. Four days later, Farrand reported to take charge. Most of the next three weeks were probably spent in preparing for the move of the capital to Richmond. Squabbles there over precious office space took some precedence over whether or not the infant Confederacy would be able to maintain its system of lighthouses.

The staff had hardly sharpened their pencils before their impossible task became apparent. The tiny U.S. Navy, only 42 ships strong, had begun its strangulating economic blockade of Southern ports. By the end of May 1861, blockaders had been assigned to the largest ports to seal in the cotton and to prevent the import of crucial was supplies. For the next few years, the blockade revealed the South’s greatest weakness and constituted the Union’s only measurable success.

The arriving federal fleet was rather slow in paying visits to light stations. Into the third week of blockading, much to their comfort, several costal lights were still in full operation. Soon, Confederate customs collectors began extinguishing - and in some cases dismantling – lighthouses to deny aid to the Union fleets. The effort may have been coordinated, or at least suggested by, Richmond, although scant Bureau records reveal no service-wide instructions to put lights out of operation. More likely, local military authorities independently asked customs officers to let the enemy drift aground without the aid of the lights. Southern mechanics hurriedly removed lamps and lenses from several towers to prevent Yankee “predators” from capturing and operating the light stations. Union gunboats responded by seizing all lighthouse property they happened upon from the lawless rebels. The coast quickly fell dark.

The Union Navy shipped most lenses and apparatus to the New York lighthouse depot for reissue, although some were put back to use almost immediately. At Chandeleur Island, Louisiana, marking the anchorages used as the Union primary staging ground for attacks along the entire Gulf of Mexico, the lighthouse was captured by the USS Massachusetts on July 9, 1861, and restored to operation on September 13th.

At Pensacola, enough carefully secreted materials were recovered to piece together a lighthouse for the Union’s first captured deepwater port.

Union and Confederate forces raided towers at the three Mississippi River passes, sometimes only hours apart. Semmes, commanding CSS Sumter sent boats on June 23 “to the different lighthouses to stave in the oil casts and bring away the lighting apparatus to prevent the enemy’s shipping from using the lights. I found that the lights at Pass a I’Outré and South Pass had been strangely overlooked and that they were still being nightly exhibited.” His men revisited one station July 11 to remove the lens, but they found that a crew from the steam sloop USS Brooklyn had removed everything of value a few hours before.

And just what was the C.S. Lighthouse Bureau doing all this time? By early July 1861, the Bureau finally struggled to its feet, steady, organized and ready to take charge. Farrand directed collectors to safeguard the expensive and vital French lenses and lamps. The lack of detailed orders left some doubt as to exactly how safe they should be made. Some collectors had already caused the lenses and supplies to be properly crated, inventoried and removed to warehouses, others simply left stations in charge of unarmed keepers. In perhaps a case of over-reaction, the Galveston collector paid a contractor $250 to entirely dismantle an 80-foot tower. The iron Bolivar Point lighthouse was taken down bolt-by-bolt and plate-by-plate, with one-inch plate probably used for the skin of a Confederate vessel. All Collectors were asked to report the status of stations in their areas of responsibility.

The Lighthouse Bureau started to implode only six months after its inception. With only one lighthouse still in operation, Farrand was released from the Confederate Treasury Department and returned to Navy duty by September 20. (His mark in history, by the way, is that of being the last major Confederate commander to surrender, about a month after Lee.) Thomas Martin was quickly appointed as Chief of the Lighthouse Bureau, ad interim, and served in that capacity until the Bureau entirely dissolved.

Martin acted quickly to preserve Confederate property for the anticipated relighting – once the Union forces recognized the futility of the blockade. In his first week on the job, he proposed a letter from the Treasury Secretary requiring collectors to remove and safeguard all property and provide inventories of all government property. He also required more formal transfers of lighthouse vessels to the Confederate Navy and Army, often with the provision that they “be returned in good order to the Lighthouse Bureau whenever required for that service,” plus or minus a few cannon-ball holes.

An End to Preservation

Extinguished lighthouse quickly became military assets. Intended for ships to sight from seaward, the lighthouses were usually the highest vantage point, well situated for defensive forces to spy on blockader movements or advancing enemy troops. Coastal lighthouses especially became sites for heavy gun emplacements or picket posts. At least one island station was turned into a bathing resort and brothel for blockade-weary Union sailors. Fine French lenses and lamps removed, they became lookouts for armies of both sides.

In most cases, lighthouses were damaged through individual acts: vandalism, accidents (the brothel burned in July ’63) or desperate attempts at destroying fortifications during a landing or retreat. Sometimes, the lighthouses simply stood in the way during exchanges of fire. One of the greatest dangers to lighthouse stations was neglect – site erosion refused to pause for the war effort. In at least one instance, the destruction was deliberate and coordinated. The general commanding Confederate forces in Texas issued explicit orders for field commanders to blow up all lighthouses if superior enemy forces attacked. Towers at Point Isabel, Padre Island, Port Arkansas, Pass Cavallo, and Matagorda Island were burned or mined with kegs of powder.

By the end of the first year of war, the Union had taken no significant ports. Indeed, the North had no campaign to be proud of. This changed when Commodore David G. Farragut steamed up the Mississippi to take New Orleans in late April 1862. His success shocked C.S. Lighthouse Bureau with the prospect that their lenses were no longer safe even in heavily fortified coastal cities. U.S. Treasury agent Maximillian F.Bonzano recovered an estimated $50,000 worth of lighthouse apparatus near the New Orleans Mint, perfectly crated and labeled for quick reassembly. In Richmond, Martin prepared letters ordering Confederate collectors to “remove the property belonging to the Lighthouse establishment under their charge to such points as in their judgment may be secure from the approach of the enemy.” The lights must be restored when victory comes to hand.

The U.S. Lighthouse Board was not inactive during this period. As strategic lighthouse sites were captured and made secure by Union forces, lighthouses were renovated and restored to operation. Technically, the Board acted under Congressional mandate to erect and operate lighthouses at specified locations, but in reality they responded directly to U.S. Navy or Army pleas for navigation aids to pursue the war effort. Unfamiliar with local, largely uncharted waters, Union blockaders operated in constant fear of grounding along the shallow Southern coast, under the guns of the enemy. Confederates prayed for offshore gales to cast the Yankee hulls into shoals within artillery range.

On July 5, 1862, an urgent dispatch arrived in Washington from the acting U.S. Collector of Customs at New Orleans requesting, immediate assistance in repairing recently captured stations. The Lighthouse Board immediately dispatched an engineer and by August 20 he had completed a survey of damage to be repaired. He also recommended Bonzano be appointed as acting lighthouse engineer to effect the repairs. Bonzano served in this capacity through the war and into the following reconstruction, supervising the reestablishment of lighthouses from Florida to Texas. Without authority to pay keepers, he arranged for Army rations and paid out a reported $15,000 of his own funds – a lifetime of income, in a time when keeper salaries averaged only a few hundred dollars per year. Most of his labor force was made up of “contrabands” – freed slaves so destitute he clothed them with Army discards.

The Dark at the End of the Tunnel

The Confederate States Lighthouse Bureau dwindled in activity until October 1862, when the last known Confederate lighthouse was extinguished on Choctaw Point at Mobile. On releasing the last keeper, Eliza Michold, the Bureau was reduced to only one employee: Thomas Martin. He continued in service, keeping track, when he could, of where lighthouse apparatus was stored, until General U.S. Grant viewed the spires of Richmond from only ten miles away.

Martin’s last annual report, submitted January 25, 1864, sadly advised Secretary Memminger that “The operation of the Lighthouse Establishment during the past year have been very limited in extent, being confined almost exclusively to the care and preservation of the Lighthouse property which has been taken down and removed to places of safety. Instructions were given to the various Superintendents of Lights to cause the illuminating apparatus and other fixtures to be carefully removed, boxed, and conveyed to different points of the interior, removed from the depredations of the enemy. I am happy to report that with two or three exceptions the efforts made in this regard were entirely successful, so that when any order may be issued by you for the resumption of the active operations of the Lighthouse Establishment (which time I trust is not far distant) no great difficulties will arise in replacing the machinery and carrying out the designs for which the Bureau were created.”

Thomas Martin was assigned two days later to the drudgery of paying war bond interest with worthless Confederate paper in the Office of the Treasurer, and then to the staff of the First Auditor of the Treasury. He was displaced from his comparatively plush offices by a jealous C.S. Surgeon General.

Lighthouse duties did not end there, however. Martin’s greatest challenge from this time onward was keeping valuable sperm whale oil out of the hands of his own countrymen. Until the Lighthouse Bureau folded, the C.S. Navy requisitioned the precious oil for gunboats, presumably for engine-room lubrication, and for lighting interior waterways not yet under Union control. The Bureau doubted the efficient use of such expensive oil, however. In one case the Confederate ram CSS Baltic had consumed 100 gallons, never even weighing anchor. “ This quantity of oil cannot be procured at any price,” Martin complained. His was a nation where the economy was in such a disaster that salt nearly equaled silver in value. Suspecting that many a card game had been played on the mess deck under a whale-oil lamp, he outright refused more requests for the precious oil “to avoid the embarrassment that would result from a total absence of oil when orders may be given to relight.” Martin was hopeful to the end that the Confederacy could survive and that his lighthouses would help restore the prosperity and dignity the South had known.

Confederate States Lighthouse Bureau records dwindled as territories came under the Stars and Stripes. The National Archives file ends abruptly with an insignificant document recording the storage of minor lighthouse property at Mobile, dated December 31, 1864. There was no Happy New Year. Thomas Martin had by that time joined a battalion of clerks and other bureaucrats, drilling each Wednesday at 1 p.m. for a desperate attempt to defend the capital.

Exactly when and how the Lighthouse Bureau entirely collapsed is not recorded. On April 2, 1865, with virtually every point on the Confederate coastline in Union hands, Jefferson Davis and several government officers forsook Richmond for a new capital in North Carolina. Was a Lighthouse Bureau Chief required there? Hardly. The last breath of the Confederacy was spent a month later in a skirmish a few miles from the ruins of the Port Isabel Lighthouse in Texas.

Fall of the Tallest Tower

No single act of destruction can typify events of the Civil War, but the loss of one lighthouse stands out as a significant catastrophe.

The Sand Island Lighthouse marked the entrance to Mobile, the South’s second-largest cotton port. At 200 feet in height, the tower was the grandest in the South, and perhaps the tallest masonry building in that nation. The Sand Island Lighthouse was erected in 1859 to overcome the shortcomings of the old Mobile Point Lighthouse at Fort Morgan. Balanced on putty-like soil, the tower was a monument to its builder, Lighthouse Board Engineer Danville Leadbetter.

Sand Island AL ca 1859

Confederate States collector T. Sanford hired a contractor to remove the nine-foot-tall, first-order lens for storage first at Mobile and later at Montgomery. The empty tower was used repeatedly as a lookout post as forces of both sides spied on each other’s strengths from aloft. Union glasses searched for weaknesses at the forts commanding the bay entrance and stood careful watch for the dreaded ram CSS Tennessee. Southern forces occasionally studied movements of the fleet from the tower.

The lens now in an enemy warehouse, U.S. lighthouse engineer Max Bonzano moved quickly to reestablish the light. He fit up a fourth order lens on December 20, 1862, under the protection of the Union fleet’s guns. He had hoped to install a first-order revolving lens soon afterward to support the anticipated invasion of Mobile.

Union men were not the only ones expecting an invasion. Fear reigned in Mobile that Union ships were preparing to pass the forts, as they had at New Orleans. They were unaware that the Union naval commander, Admiral David G. Farragut, was so frustrated in the siege of Vicksburg that he could not release enough ships to carry out any threat against Mobile.

Under orders from the engineer of the defenses of Mobile, a small Confederate force under Lt. John W. Glenn rowed from Dauphin Island’s Fort Gaines to Sand Island on January 31 to remove the offending tower. In a tactical blunder, he decided to first burn the keeper’s dwelling and four other buildings. The blockading USS Pembina spotted the flames and fired on the Confederates, forcing them to retreat. But Glenn returned to the tower on February 22, this time under the cover of darkness. By dawn, he had secreted a total of 70 pounds of black power at various places in the tower.

At 3 P.M., he lit the fuse and then left for Fort Gaines. “Nothing remains but a narrow shred [of brickwork] about fifty feet high and from one to five feet wide,” he boasted in his official report, adding, “The first storm we have will blow that down.” By incredible and sad coincidence, his report was addressed to Confederate Colonel Danville Leadbetter, the former U.S. Lighthouse Board engineer who had labored to create the “magnificent tower at Sand Island” only three years before.

The Future of the Past

Reconstructing events in the South during the Civil War is a monumental job, made difficult by an agonizing lack of organized, authoritative documentation. Confederate records amount to less than a cubic foot of papers, most of which are pay slips for keepers. Confederate Engineering reports of lighthouse damage, if there ever were any, apparently never reached Richmond, or perhaps never survived Richmond. Union civil records are limited mostly to the Lighthouse Board’s Annual Reports to Congress, which present a very slanted view (justifiably so, considering the times) with bands of lawless rebels blasting towers to rubble. On-scene Union reports were destroyed in a Commerce Department fire in the 1930’s, before the National Archives consolidated these records. Military operations exist in excruciating detail, to the point that they measure in miles of Archives shelf space and in hundreds of cubic yards. Undocumented local legends abound on the subject, often in conflict with scraps of available fact.

The American Civil War, the greatest single chain of events affecting our Southern lighthouses, deserves exhausting research and documentation.